The Trinitarian gospel offers a transformative lens for understanding scripture, shifting away from legalistic interpretations toward a vision of God’s love, adoption, and restoration. This perspective challenges traditional frameworks like the heaven and hell framework and the legalistic gospel, revealing a deeper narrative rooted in God’s eternal purpose. By exploring the kingdom narrative, adoption theology, and the true meaning of God’s justice, holiness, and salvation, the Bible’s message comes alive as a story of healing and inclusion in God’s family, not a legal transaction to escape punishment.

Understanding Biblical Frameworks: From Heaven and Hell to Adoption

The way scripture is approached depends on the underlying assumptions or lenses, used to interpret it. The heaven and hell framework assumes the Bible’s primary purpose is about escaping hell to reach heaven, viewing God’s creation of humanity as a test to determine eternal destinations based on actions. This lens oversimplifies the biblical narrative, reducing every passage to a question of avoiding hell. However, the Bible’s core message is not about escaping punishment but about something far richer.

A more accurate lens is the kingdom narrative, which sees both the Old and New Testaments as centered on God’s kingdom coming to earth. Rooted in Genesis 1, where God creates humanity in His image to have dominion, this perspective captures God’s broader plan for creation. Yet, the ultimate framework is adoption theology, as Ephesians 1:4 declares: “Long before he laid down earth’s foundation, he had us in mind, had settled on us as the focus of his love.” Adoption theology defines God’s purpose as expanding His family, inviting humanity into the Trinitarian gospel—a relationship with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Through adoption, people become mature sons, born of God’s seed, sharing His divine nature and calling Him Father literally, not just metaphorically. This shifts the focus from fear of hell to inclusion in God’s triune family, becoming channels of His fullness.

Redefining Sin, Salvation, and God’s Justice

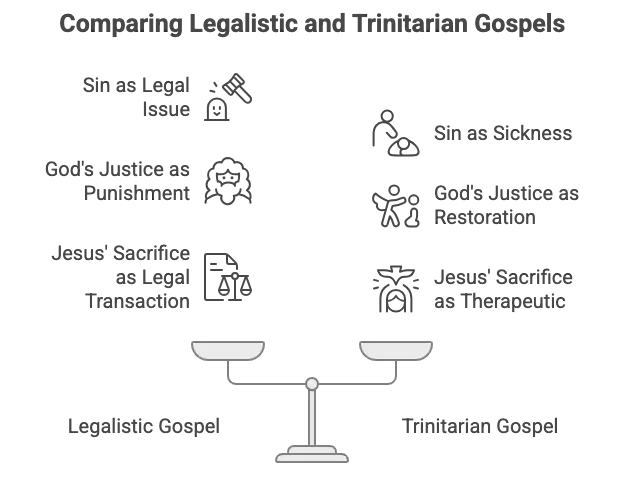

The legalistic gospel distorts the perception of God, portraying Him as a judge with a split personality: love, grace, and mercy on one side, but holiness, justice, and wrath on the other. This view, shaped by humanity’s fall into the knowledge of good and evil, sees sin as corruption—a legal issue requiring punishment. The legalistic gospel claims God’s holiness demanded punishment for sin, which Jesus took on the cross to balance love and justice, making forgiveness and justification legal transactions. In this view, God withheld punishment in the Old Testament (mercy) but occasionally lashed out, as seen in inconsistent punishments like stoning a man for picking sticks on the Sabbath while sparing David for eating holy bread. In the New Testament, Jesus absorbs all wrath, so believers receive grace. However, this creates contradictions, implying the Father changed after the cross or that Jesus’ sacrifice saved humanity from the Father’s wrath—a troubling idea.

In contrast, the Trinitarian gospel redefines sin, salvation, and justice. Jesus described sinners as blind, sick, lost, and dead, saying, “The blind cannot lead the blind,” “Only the sick need a physician,” and “The Son of Man came to seek and save the lost.” Sin as sickness, not a legal one, and punishment cannot heal it. A blind person needs sight, a sick person needs healing, a lost person needs to be found, and a dead person needs to be raised. Salvation meaning in the Bible, from the Greek word “sozo,” is healing, deliverance, and prosperity, not a legal ledger balance. When Jesus told a woman, “Your faith has saved you,” it meant “Your faith has healed you.” Biblical righteousness is transformation, not legal clearance, as seen with Abraham, whose faith led to a son, and Rahab, who was saved from Jericho’s destruction.

The New Testament never states God poured out wrath on Jesus or punished Him. Phrases like “God punished Jesus for our sins” are read into verses like “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?” due to legalistic lenses. Instead, 2 Corinthians 5:21 says Jesus “became sin,” taking humanity’s sin and death—not because He sinned, but to die humanity’s death and heal its godforsakenness. Jesus’ sacrifice is therapeutic, addressing the corrupted human heart to restore it to know the Father. The prodigal son parable in Luke 15 illustrates God’s justice as love and restoration, not punishment. The father embraces the son, ignoring his confession, and throws a party, declaring, “It was right that we should make merry and be glad, for your brother was dead and is alive again, was lost and is found.” True repentance happens in the father’s embrace, restoring sonship—a picture of God’s justice as alignment with His original design.

The Trinitarian Gospel: Holiness, Love, and a Warning

The legalistic gospel misdefines holiness as the absence of sin, requiring sin to define God’s nature. This is flawed because God was holy before creation. Holiness definition is uniqueness—one of a kind, not common—rooted in the Trinity’s loving, other-centered relationship, free of blemish or obligation. Ephesians 1:3-4 says God chose humanity to be “holy and without blame before Him in love,” made whole by His love. Jesus, as the exact representation of the Father (Colossians 1:16, Hebrews 1:3, John 1:18), reveals not just love but also holiness and God’s justice, showing they are not opposing forces. Matthew 12:18-20 describes Jesus’ justice as compassionate, not breaking a bruised reed or quenching a smoking flax. Isaiah 30:18 confirms, “The Lord will wait, that He may be gracious to you… for the Lord is a God of justice.”

The Trinitarian gospel is the Trinity’s fiery love reaching into human darkness to heal and restore. Jesus’ sacrifice was not to appease the Father but to reconcile the world to God (2 Corinthians 5:19). God was in Christ, penetrating the black hole of human brokenness to heal, not to balance a legal ledger. This gospel is “too good to be true,” revealing the Father’s love while humanity was still in sin. God’s wrath targets what destroys humanity—sin and religion—not sinners. Jesus condemned religious spirit in leaders who obstruct God’s love, not sinners. Sin does not separate God from humanity; He reached Adam in sin and Jesus when He became sin. However, the religious spirit shuts the door on God, perpetuating the legalistic gospel. The early church fathers and Nicene Creed emphasized the Trinity’s love, not legalism.

What if the gospel is not about escaping punishment but about being embraced by a God who runs to you, like the father in the prodigal son parable, to heal your brokenness and welcome you into His family? Reflect on how this Trinitarian gospel—rooted in love, holiness, and God’s justice—changes the way you see God and yourself. Let this truth sink in: God’s love is not a legal transaction but a transformative embrace that makes you whole.